By Mariana G. Bego

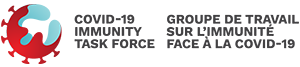

Bats are the likely ancestral host of the new coronavirus that rapidly spread out of China and across the world. Bats are the natural viral reservoir for many viruses, including several coronaviruses (see Figure 1). As a ‘reservoir’, bats infected with coronaviruses are often not affected by them – they tolerate viruses without getting sick – but can infect other animals, including humans. It is not clear at the moment if the virus that causes COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, came directly from bats or if it passed through an intermediate host first. The leading theory for the origin of the current pandemic virus is that a virus crossed from bats into another animal quite some time ago and there, it mutated into a variant that can infect humans.

Figure 1: Primary reservoirs and intermediate hosts of human coronaviruses and their cross- species transmission leading to infections in humans.

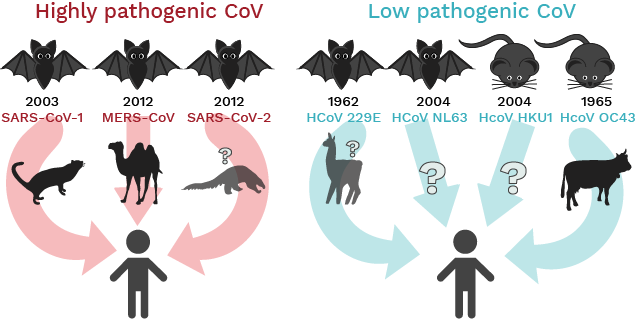

A virus that is a close match to SARS-CoV-2 was discovered in bats at a wildlife sanctuary in eastern Thailand. These results were published in a Nature Communications article released last week. This report extends the area in which SARS-CoV-2-related viruses have been found in Asia to a distance of almost 5,000 km (or 3,000 miles, see Figure 2). The authors collected samples from a colony of ~300 bats and 10 pangolins from three Wildlife Checkpoint stations in Central and Southern Thailand with unknown countries of origin. These pangolins were confiscated from illegal traders and quarantined under the Wild Animal Reservation and Protection Act. In these samples, researchers found antibodies that were able to recognize and neutralize the current pandemic virus. This implies that the virus these animals carry is morphologically, and potentially functionally, very similar to the virus causing the current human pandemic. These results provide further evidence that SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses are circulating in Southeast Asia and authors predict that similar coronaviruses may be present in bats (and other possible intermediate hosts) across many other Asian nations and regions.

Figure 2: Regions in Asia where SARS-CoV-2-related coronaviruses have been detected to date.

Find the article here

What makes bats so unique as viral reservoirs?

There is abundant evidence that bats harbour more viruses per species than any other mammal on Earth. However, they do not get sick as they have ‘learned’ to co-exist with a variety of viruses, while actively transmitting them to other animals. So, what is so unique about bats? Well, for one, they are the only mammals that can fly. Compared to similar-sized placental mammals, bats have extensive lifespans – they can live up to four times longer than their terrestrial cousins. Cancer incidence in bats is rare and even completely absent in some species. They have been shown to have improved DNA repair machinery and immunocompetence, with a reduced propensity to inflammation. All these virtues may be tied to a single element, flight! Well, as it turns out, a lot of energy is needed to fly. And this high metabolic demand causes a significant amount of DNA damage. As part of the adaptations required to allow them to fly, bats have evolved a particularly tuned DNA sensing and repair machinery. This machinery repairs their DNA quickly and effectively, hence the low incidence of cancer and extreme longevity. But also, it allows their cells to respond to infections without overreacting, creating a perfect environment for both host and virus. Understanding immune control in bats, the viruses they carry and the molecular and ecological forces driving viral spill-over to other mammals will hopefully arm us with tools to respond to the next outbreak, faster.

Read more about bat-borne viruses here.

To hunt or not to hunt, for viruses!

There is still significant debate among the scientific community whether outbreaks could be predicted and prevented from routinely sampling various animal reservoirs, including bats. Initiatives like the Global Virome Project aim to fully characterize viruses harboured by animals known to carry pathogens able to infect humans. The cost of such an enterprise would be about 3.7 billion USD and would take place over the next 10 years. These types of initiatives can have a huge impact from how we focus basic research to overall outbreak preparedness. Critics argue that while sequencing thousands of viruses would be great for science, such an effort may not be enough to prevent the next pandemic. Back in 2013, viruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 were already identified in wild bats, and we knew that they possessed the ability to infect human airway cells. Unfortunately, that knowledge did not stop the current COVID-19 pandemic from taking hold. But if we do have the knowledge of potentially very dangerous viruses circulating in the wild, what should be done differently next time around?

Read more about the Global Virome Project here.