Ullah I, Prévost J, Ladinsky MS, Stone H, Lu M, Anand SP, Beaudoin-

Bussières G, Symmes K, Benlarbi M, Ding S, Gasser R, Fink C, Chen Y, Tauzin A, Goyette G, Bourassa C, Medjahed H, Mack M, Chung K, Wilen CB, Dekaban GA, Dikeakos JD, Bruce EA, Kaufmann DE, Stamatatos L, McGuire AT, Richard J, Pazgier M, Bjorkman PJ, Mothes W, Finzi A, Kumar P, Uchil PD. Live Imaging of SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Mice Reveals that Neutralizing Antibodies Require Fc Function for Optimal Efficacy. Immunity (2021). doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.08.015.

The results and/or conclusions contained in the research do not necessarily reflect the views of all CITF members.

An international multisite research collaboration, including CITF-funded researcher Dr. Andrés Finzi from the Université de Montréal, used genetically modified mice that mimic COVID-19 disease in humans to study how antibodies from people who have recovered from COVID-19 could prevent severe disease in other people. The authors concluded that these antibodies were effective in not only blocking SARS-CoV-2 infection, but also in allowing mice infected with a lethal dose of the virus to fully recover. This work, partially funded by the COVID-19 Immunity Task Force, has now been published in Immunity.

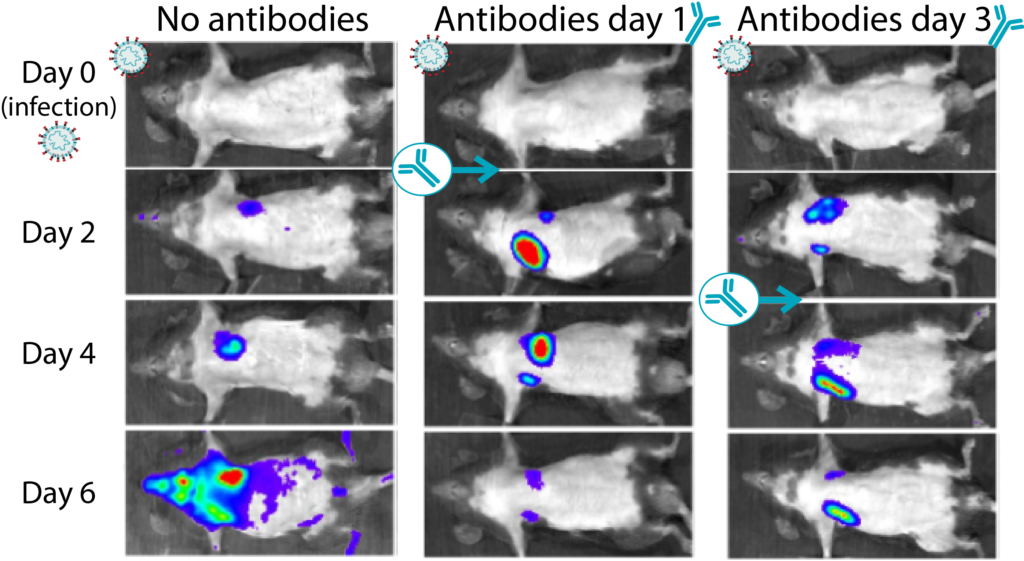

For this study, mice were infected with SARS-CoV-2 virus expressing a bioluminescent reporter, making it possible to visualize the infected tissues in the live animals. The use of this small animal model allows scientists to answer questions that otherwise would go unanswered as human test subjects cannot be used. They used a technique called live bioluminescence imaging (BLI), which allowed the team to take pictures inside the mice to identify which tissues were infected, over time. Mice that were genetically modified to express the human receptor for SARS-CoV-2 in all their cells were used, meaning they could be infected in similar ways to humans.

Researchers then injected some of the mice with neutralizing antibodiesAntibodies that bind to the surface structures of a pathogen, preventing it from entering and infecting its host cells. (antibodies from a donor who have recovered from COVID-19 from the team’s CR-CHUM cohort) and compared the results to mice not given any treatment. In mice who received no antibodies, SARS-CoV-2 spread from the nasal cavity (the infection point) to the lungs, followed by a systemic spread to various organs including the brain, and subsequently culminating in death. The authors demonstrated that mice that were administered neutralizing antibodies before being injected with SARS-CoV-2 were resistant to infection. In another experiment, they administered antibody treatments after infection to determine how they acted. The treatment with neutralizing antibodies also cleared the virus from established infections when administered within the first three days post-infection (See Figure 1).

Figure 1: Transgenic mice infected with bioluminescent SARS-CoV-2 virus were protected after receiving antibody treatment. Infected tissue can be observed according to the intensity of light they emit (with purple being lower amounts of infection and red the highest areas of infection). This figure shows only the mice given no treatment or neutralizing antibodies after being infected with SARS-CoV-2. Mice were infected at day 0 and received either no antibody or antibody treatment on day 1 or 3 post infection. For each example depicted, images from the same animal are shown for the day of the infection (day 0) and days 2, 4 and 6 post infection. By day 6, the animals that received antibody treatment had significantly less virus in their tissues than untreated animals. Image adapted from Ullah et al. Permission to use this image given by P. Uchil.

Finally, the authors evaluated the mechanisms involved in the potent antiviral effect of the neutralizing antibodies. They concluded that these antibodies did more than simply neutralize SARS-CoV-2. They demonstrated in detail in their paper, that for these antibodies to fully exert their protective capacity, they need to be able to interact with several types of immune cells including monocytes, neutrophils, and natural killer cells (a mechanism known as Fc-mediated effector functions). This interaction was needed to dampen the general inflammatory responses that can actually make the disease worse. The authors proposed that their small animal model can be used to identify effective antiviral therapies that can be rapidly extrapolated for clinical use in humans.